What Makes a Dog a Dog?

A deep dive into your dog’s canine traits and how you can use that information to create a better life together.

20 minute readIn order to be a great dog parent, you first have to understand who your dog really is. Respecting your pup as a canine will help you keep him safe, train him to fit into your life, and develop the unbreakable bond everyone talks about.

Here’s a deep dive into what makes your dog a dog. Does your new family member think like a wolf? What are his natural instincts? And how can you use that information to create a better life together?

tl;dr

- There's debate when and where dogs were first domesticated. Ancient wolves probably scavenged for food around our ancestors, who used them for hunting and protection.

- Today’s dogs are not modern wolves. The main difference? Dogs have an incredible social ability. They routinely bond with different species.

- There's little evidence dogs do things out of a desire to “be dominant” over their owners. The term is often misapplied as a motivation for social interactions.

- Dogs don’t experience the world like humans do. A canine’s primary sense is smell, followed by hearing, and sight.

- Dogs primarily learn through associations. The most common learning theories in dog training are operant conditioning, classical conditioning, and social influence.

- Your dog learns best under an optimal level of alertness. Consider his emotions and provide opportunities to make his own decisions.

- Dog body language is nuanced. When trying to figure out how your dog feels, you should pay attention to his tail, posture, muscle tension, facial expressions, ears, eyes, and hackles.

- Sometimes dogs give “mixed” signals when they feel conflicted. Gauge all of his body language cues together in a given context.

- Dogs and humans are similar in a key way: We’re both social mammals. We have a basic need to bond with others. This is the core of the dog-human relationship!

Contents

History of the domestic dog

The exact timing, location, and cause of dog domestication is a matter of debate. Most scientists believe they branched off from a now-extinct species of wolf between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago in Eurasia. Around 7,000 years ago, village dogs could be found everywhere humans lived. It wasn’t until the 19th century that many of the modern breeds we recognize today emerged.

How did people domesticate dogs?

The dog was the very first species to be domesticated. Humans were partnering with man’s best friend even before the rise of agriculture! To this day, dogs are the only large carnivore that routinely live among people as members of the family.

There are many theories about how modern dogs came to be. Two popular ones are that:

- Ancient dogs domesticated themselves by scavenging for food around groups of people

- Humans selectively bred wolves as hunting partners and protectors

The truth is likely a combination of both.

Did wolves domesticate themselves?

This theory proposes that wolves “chose” to become domesticated. The smell of food attracted them to human camps. Only the wolves who were bold enough to venture near people were able to scavenge extra resources and increase their odds of reproducing. This meant that traits like decreased aggression and a higher threshold for stress were naturally selected for over time. Future generations became more and more tame.

Since genes can’t be separated into “personality” and “appearance”, physical changes occurred alongside these temperament shifts.

Did we selective breed ancient wolves?

There is also evidence that humans selected certain traits in ancient wolves. Researchers suggest that ancient people and dogs developed a hunting partnership. Canines could not only assist in capturing prey. They could also provide defense from competing predators.

Together our ancestors had better access to food. Over many generations, the wolves who worked best alongside people had the best chances of reproducing. This was due to both natural strength from increased nutrition and human intervention like access to shelter or even intentional mating decisions. In short, the most cooperative tame wolves became dogs over many generations.

Breeding as we know it today—with closed gene pools, health testing, and carefully selected lines—has only existed for the past few hundred years. Before that, most dogs bred freely aside from some specific pairings chosen by working handlers.

Humans and dogs have coevolved together

While much of the domestic dog’s history remains murky, one thing is clear: The dog-human bond has genetic components that date back generations and generations.

- Dogs have evolved specialized skills for reading human social cues. They might even be more cognitively similar to us than some of our closest genetic relatives! Domestic dogs can follow human pointing gestures, discriminate between our facial expressions, and mirror our emotions from a young age.

- Many dogs actually respond more readily to signals from people than from their own species. In his book Dog is Love, Dr. Clive Wynne summarizes multiple experiments to test the bond between people and their dogs (one even saw if they care more about food or social interaction). Researchers compared domestic dog performance with that of hand-raised wolves in the same setups. Who performed better? You guessed it. Our pets.

- This connection goes both ways. Most people can tell from his bark alone whether a dog has been left by himself, is playing with another dog or person, or is being approached by a stranger.

- An extensive number of genes show signatures of parallel evolution in humans and our dogs. Ancient wolves accompanied our ancestors into a range of new environments. They evolved alongside us accordingly.

- Some of these genes act on the serotonin system in the brain. They’re correlated with reduced aggressive behavior when living in a crowded environment, something that’s important for both modern humans and our pets.

- Extended eye contact increases oxytocin levels in both dogs and their caretakers. Often called “the love hormone”, this chemical is most known for its role in maternal bonding. This further supports the coevolution of the dog-human relationship.

All that said, it’s still important to realize your dog can’t actually read your mind. While we’ve thrived together for thousands of years, dogs and humans experience the world differently (more on that in a later section). Your dog has great intuition about your emotions! But you can’t expect him to know exactly what you’re thinking, when you’re thinking it, and why.

Dogs aren’t miniature wolves

Genetic studies suggest that modern dogs and wolves descended from a now-extinct common ancestor. While they share ancient lineage, the dogs we know and love branched off from wolves thousands of years ago. They are not the same thing! Two key differences are that domestic dogs have an incredible ability to bond with members of different species and retain more juvenile traits throughout adulthood.

That said, today’s grey wolf is the domestic dog’s closest living relative (ours are the bonobo and chimp).

Domestic dogs are social with members of other species, not just their own

Dogs generally show reduced fear and aggression compared to other canines. Some of the behavioral differences between dogs and wolves may be explained by variation in the same genes that are associated with Williams-Beuren syndrome in humans. What does Williams-Beuren cause? Hyper-sociability—which would have been important during domestication to live around humans and eventually other animals like livestock.

There is also a link between the domestic dog’s oxytocin receptor and their social behavior. DNA differences have been found between wolves and dogs, with variations between specific breeds that seem to affect general sociability.

Finally, domestic dogs have a less pronounced fight-or-flight response than modern wolves do. The genes that affect their adrenaline and noradrenaline pathways are different. Our dogs have higher stress thresholds.

All of these things enable dogs to be incredibly social with other species. This is not common among other canines.

Dogs retain more juvenile traits into adulthood

Neoteny, also called juvenilization, is the slowing of an animal’s physiological development. Modern humans are neotenized compared to other primates. Compared to other canines, so are our domestic dogs.

- Selecting for juvenile behaviors makes it easier to domesticate a species. Some of these traits we see in our dogs include increased playfulness, dependency, and care seeking. We see these behaviors in young and adolescent wolves, but they don't commonly occur in adults.

- Humans also find physical neoteny to be cute. And the cuter an animal is, the more likely we are to care for it! Things like short snouts and wide-set eyes are associated with puppies. We’ve intentionally bred these into some particularly neotenized dog breeds like Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and other members of the toy group.

- While many of our dog’s traits are associated with juvenile wolves, domestic dog puppies are still considerably different from their wolf counterparts. Your pet is not just a baby wolf! Young dogs spend more time sleeping, have reduced coordination, and are often cleaner (less likely to soil themselves or sleep in their own filth). These signals of innocence further cement our bond by triggering our human drive to nurture.

What instincts does my dog share with other canines?

While domestic dogs aren’t wolves, they do **have some deeply ingrained canine drives.

Dogs are scavengers

Canines are biologically inclined to sniff and dig around the environment. As much as we’d like them to, our dogs don’t automatically understand our human taboo on grabbing day-old chicken bones off the sidewalk. Eating things they find on the ground feels normal to a dog.

Dogs are also predators

While selective breeding influences the exact type and intensity of their instincts, most dogs have at least some prey drive. That means they’re attracted to fast-moving objects (especially small animals like birds and squirrels). Dog parents can use this to our advantage during walks, play, and training games.

Even young puppies will emulate parts of the predatory sequence during play: searching (sometimes called orienting), stalking, chasing, fighting (often broken down into “grab-bite” and “kill-bite” parts), celebrating, and consuming.

Dogs have a large radius of social connection

Dogs are comfortable venturing farther away from their packs than us people.

- Humans and canines have different natural walking speeds. With variation across breed and age, dogs generally cover ground at about twice our pace. No wonder walking next to us on a leash is a foreign concept for most puppies!

- Since they rely less on vision, canines aren’t as concerned about going out of sight (more on your dog’s primary senses in the next section). They can feel socially connected to their family from a greater physical distance—which explains why they often want to explore ahead of us on walks.

Dominance isn’t your dog’s driving force

“Dominance” has been a dog training and ownership buzzword for decades. Dominance does exist in canines and in humans, but it isn’t as straightforward or strict as we initially thought.

- There is little evidence that dogs do things out of a desire to “be dominant” over their owners. The term is often misapplied as a motivation for social interactions.

- Dominance is a property of relationships, not individuals. It’s flexible between situations.

- Dominance is largely based on control of resources. This means we’re automatically in charge of our dogs’ lives. (No need to follow outdated “alpha” training protocols.)

Most feral dog and wolf packs function similarly to nuclear human families. Being in charge is about caring leadership, not physical force.

How does my dog experience the world?

Dogs don’t experience the world like humans do. A canine’s primary sense is smell, followed by hearing and sight. We might notice completely different things in the exact same environment! Dogs also have an associative rather than episodic memory. They learn patterns and develop “pictures” of certain situations as opposed to recalling specific events.

Understanding your dog’s perception helps you:

- Give him time to explore the world in ways he finds meaningful. This ultimately enriches both of your lives.

- Imagine why a certain environment might be stressful for him. This can make you more empathetic when he gets distracted or seems uneasy.

- Consider what competing motivators might affect a training session. The park might seem empty and quiet to you, but your dog might smell dozens of interesting things.

- Communicate with him more clearly in ways he can understand. We naturally fall back on human tendencies. While we know dogs have evolved to pick up our social cues, we still can’t expect them to see things from far away or completely turn off their noses.

Your dog’s primary sense is smell

Humans are a primarily visual species. Dogs, on the other hand, have much poorer vision. It’s blurrier and with diluted colors. But their sense of smell is at least 10,000 times more powerful than ours.

They also beat us out in hearing. Dogs are able to pick up on nearly twice as many frequencies as we can (that’s how “silent” dog whistles became a thing). They can notice sounds as much as four times farther away.

- Every time you walk down the street with your dog, remember that while you can see the details of the tree’s leaves and your neighbors’ mailboxes, he can smell every prey animal, other dog, and person within a huge radius.

- When he barks “at nothing” in the evening, remember that he may have heard a strange noise down the road.

- When he has to sniff his new toy (or bed or bowl or crate or other belonging) before using it, remember that while you picked it out based on aesthetics, he is paying attention to its scent.

Your dog has an associative memory

Dogs don’t just perceive the world differently than us in the moment, they also remember it differently after the fact. Canines have an associative memory, rather than an episodic one.

An episodic memory means humans recall specific events and surrounding context. We remember the time, place, and exact order of entire interactions (whether or not our recollections are accurate is a different story).

An associative memory means dogs remember general associations. They learn patterns and develop “pictures” of certain situations as opposed to recalling specific instances.

- You might remember each individual walk you took with your dog this week.

- Your dog remembers broader patterns. He knows that you’re about to leave when you grab your shoes and his leash, but he doesn’t think about the exact path you took.

Dogs also seem to have poor short-term recollection. Yelling at your puppy for something he did twenty minutes ago likely won’t do either of you any good.

How does my dog learn?

We know that our dogs have different senses than us and form associations rather than episodic memories. How do they process new information? The most common learning theories in dog training are operant conditioning, classical conditioning, and social influence. Canines can also experience single-event learning. You can set your dog up for training success by creating an optimal level of stress, considering his emotions, and providing opportunities to make his own decisions.

Your dog experiences a range of emotions

Dogs aren’t robots. Your pup has emotions! While we can never completely understand our pets’ subjective experiences, evidence supports their feelings:

- Dr. Gregory Burns has conducted multiple studies on canine perception, decision making, and brain function. When put into an MRI machine, the same areas of a dog’s brain light up as a human’s in similar contexts.

- Dogs likely experience many of the emotions we do. While the jury is out on some complex feelings like guilt, most researchers believe canines can feel joy, sadness, love, anger, fear, and more.

- Why is this relevant to dog training? Emotions are linked to cognitive skills in humans. It follows that they affect our dogs’ ability to learn, too.

Learning theories in dog training

Operant conditioning

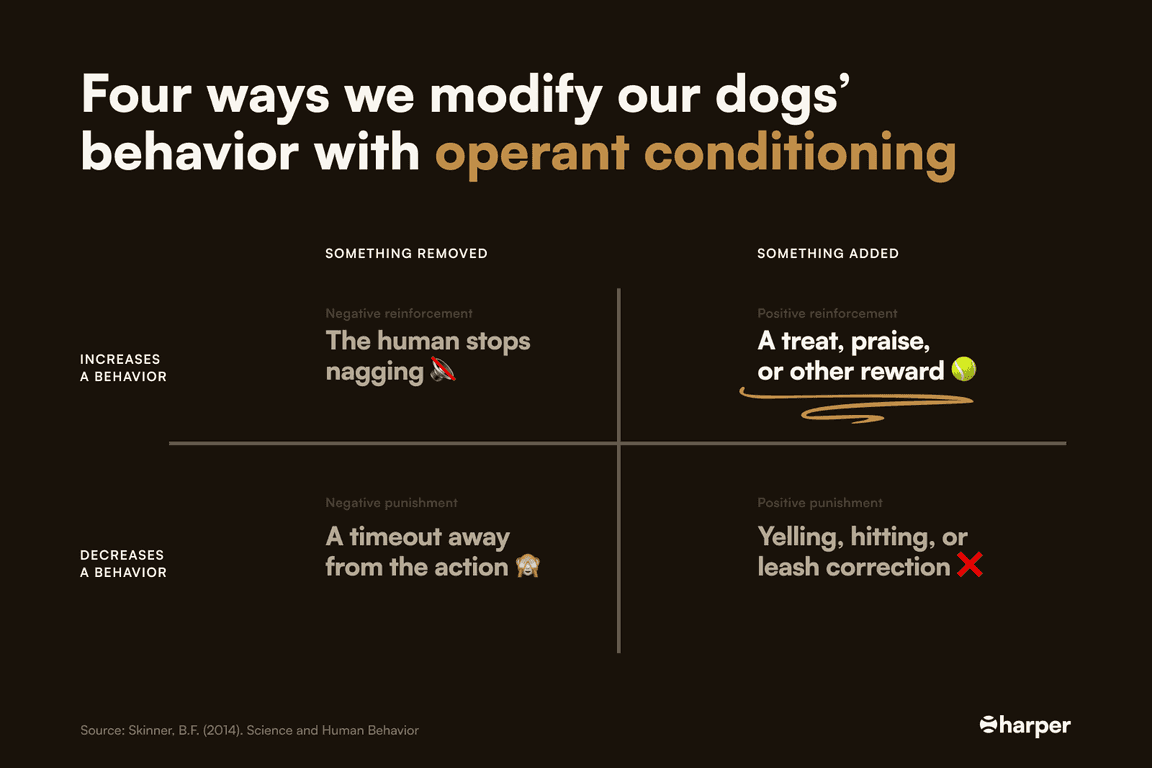

Operant conditioning is a learning theory where an animal makes an association between a particular behavior and a following consequence. That consequence affects how often they perform the behavior moving forward.

Operant conditioning is not all there is in dog training, but it’s often the driving conceptual foundation.

There are four operant conditioning quadrants based on two criteria:

- You either want a behavior to increase or decrease

- You either add something or remove something to achieve that result

If you add something, it’s called “positive” (even if what you’re adding is unpleasant). If you take something away, it’s called negative. In operant conditioning, “positive” does not mean good and “negative” does not mean bad!

If you’re increasing a behavior, it’s called reinforcement. If you’re decreasing a behavior, it’s called punishment.

| Add stimulus | Remove stimulus | |

|---|---|---|

| Increase behavior | Positive reinforcement (+R) | Negative reinforcement (-R) |

| Decrease behavior | Positive punishment (+P) | Negative punishment (-P) |

While operant conditioning can create entirely new behaviors, it’s easier to reinforce tendencies that already exist than to create them from scratch. Think about teaching your dog (who has a natural drive to chase prey) to retrieve a ball versus teaching a rabbit to do the same. You might achieve the same behavior through well-timed reinforcement. But the underlying emotion will never be the same.

Some examples of operant conditioning:

- When your puppy jumps up on you in greeting, you turn away and ignore him. This is negative punishment. You are removing something he wants (your attention) to decrease a behavior (his jumping).

- You give your dog a treat or favorite toy when he follows your sit command. This is positive reinforcement. You are adding something he wants (food or play) to increase his behavior of sitting on cue.

Classical conditioning

Most traditional dog training is accomplished through a focus on behavior. Classical conditioning always happens alongside operant conditioning, though!

Classical conditioning is a type of learning that occurs unconsciously. It’s about feelings and impulses rather than thoughtful behaviors. You condition your dog's innate reflexes — things he can’t control — to specific signals. Over time, your dog reflexively reacts to the signal itself.

Some examples of intentional and unintentional classical conditioning with dogs:

- Every time you finish a yogurt container, you let your dog lick the empty cup. He eventually starts to salivate whenever he sees you eating yogurt.

- When you put on your shoes, you take your dog outside for a walk. He begins to feel excited when you reach for your shoes.

- Your dog is afraid of thunder. Every time there is a boom, you give him his favorite treat. Over time, he starts to associate the positive anticipation of a reward with the previously negative sound of the storm.

A simple way to differentiate between operant and classical conditioning? Operant conditioning is primarily focused on behavior. Classical conditioning often focuses on emotion.

Social learning

Dogs can also learn through observation. This happens in a range of contexts, both from watching other dogs and us humans. DNA differences between wolves and dogs show greater synaptic plasticity in our pets. That’s the cellular correlate of learning and memory! These improved abilities helped lower the domestic dog’s fear around humans. Instead of being afraid of other species, they learn from us.

Social learning is generally less risky than individual trial-and-error approaches. This gives animals who practice it an evolutionary advantage. Instead of experiencing a negative consequence directly, a puppy can gain valuable information by observing a littermate or family member.

Some examples of social learning:

- Your dog watches you turn the pantry door handle to access his food. Eventually, some dogs learn to pull the lever down themselves.

- You’re always happy to see your friends when they come over. Your dog learns to share in your excitement.

- On the flip side, you hate bugs and snakes. From watching you jump and shriek, your dog learns to be wary of them too.

Single-event or one-trial learning

While dogs generally learn through associations built over time, canines can experience one-trial learning. A single traumatic experience might have a lasting impact for the rest of your dog’s life. This explains why:

- Some puppies become afraid of all other dogs after being attacked once.

- A bad exposure in a puppy’s fear period can turn into a long-term phobia.

- Dogs might avoid areas where they were injured once, like a corner of the yard that housed a hidden beehive.

Single-event learning is unlikely in most traditional training contexts (you won’t teach your dog a reliable sit command in just one repetition, sorry). It does have implications for a puppy’s socialization though. Err on the side of caution when exposing your dog to new situations. Remember that quality of experience matters more than quantity.

How can I help my dog learn most effectively?

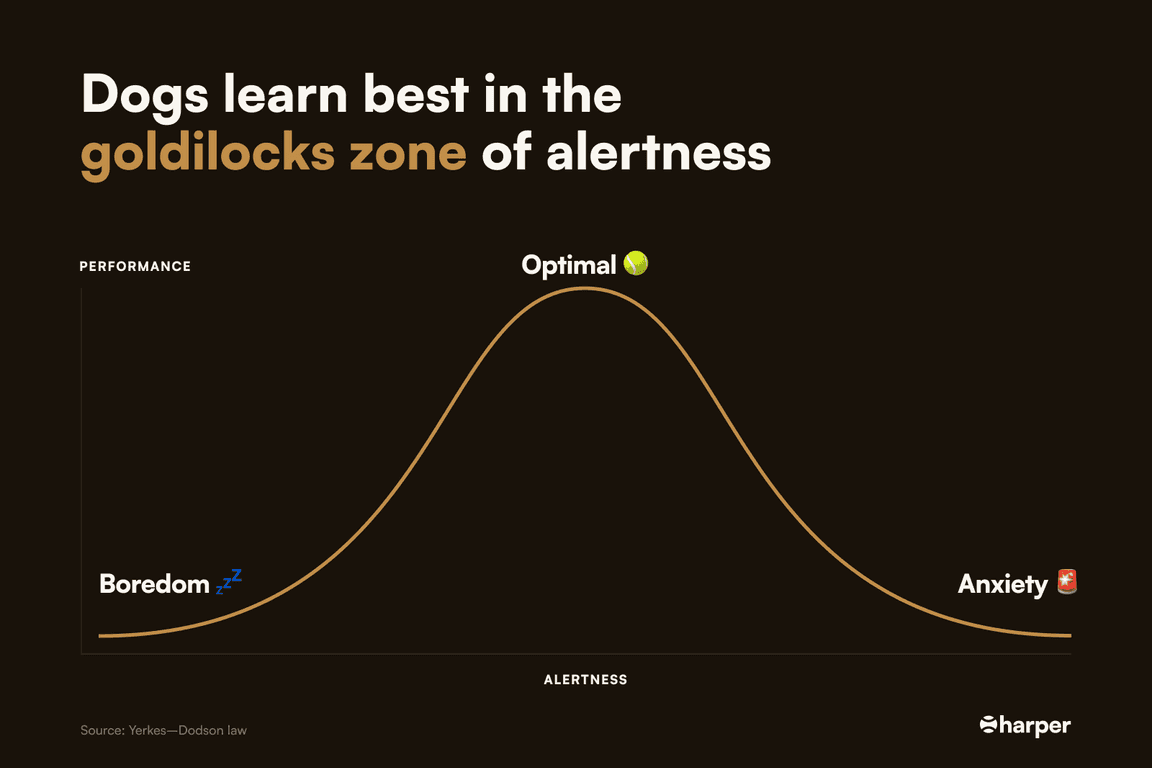

Aim for an optimal level of stress or arousal

We often hear that stress is bad. It’s not always negative, though! The Yerkes-Dodson law proposes that learning performance increases with mental or physiological arousal (read: stress), but only up to a certain point. If the stress level becomes too high, performance decreases again.

Find the sweet spot where your dog is engaged and alert without feeling overwhelmed.

Consider your dog’s emotions

We can never fully separate emotions from behavior. They drive each other, working together to color our experiences and interactions with the world. While it’s natural to focus on your dog’s outward behavior, it’s important to consider how he might be feeling, too.

- Instead of simply asking your dog to exercise impulse control around visitors, consider how you might help him experience calmer emotions when guests arrive to the house.

- You might want your dog to stop barking when in his crate. You can do that by improving his genuine comfort when being left alone.

- If your pup is scared in a busy environment, he won’t be able to pay attention to you. It might seem like he’s being stubborn. Chances are he’s just overwhelmed.

Let your dog make his own decisions when possible

Management and structure are important when raising a dog. Thoughtful daily routines are your friend.

That said, your dog will learn best when given some opportunity to make his own decisions. In safe situations, this will allow him to see the results of his actions more clearly. Freedom can also be motivating. The more choice you give your dog, the more empowered he feels. This can lead to greater self expression, joy, and cooperation than if you constantly guide him into specific behaviors.

What does my dog’s body language mean?

Dog body language can be nuanced. When figuring out how your dog feels, you should pay attention to his tail, posture, muscle tension, facial expressions, ears, eyes, and hackles. Sometimes dogs give “mixed” signals when they feel conflicted or express individual traits. It’s important to gauge all of his body language cues together in a given context.

Canine body language basics

When evaluating your dog’s body language, you should pay attention to his:

- Tail: A wagging tail doesn’t always mean your dog is happy! It suggests emotional arousal. Your dog’s tail motion could indicate excitement, frustration, or even nervousness.

- Posture: Much like humans, dogs “make themselves small” by cowering when scared. They hold themselves forward when they’re interested in something or facing up to a threat.

- Body tension: The rigidity of your dog’s body matters too. Loose movements are associated with comfort. Tension suggests more intense (often negative) emotions.

- Facial expressions: Relaxed features, especially paired with an open mouth, mean your dog is content. Tightly pulled back lips or a furrowed brow indicate stress. Yawns are often a sign of anxiety.

- Ears: Even floppy-eared dogs can adjust their position. Neutral ears are usually slightly back or out to the sides. Pinned ears suggest anxiety, discomfort, or submission. Erect, forward ears (often paired with forehead wrinkles) show interest or fixation.

- Eyes: The intensity of your dog’s gaze, as well as where he’s looking, can tell you how he feels. Soft eyes suggest calmness while hard stares are often a cause for concern. “Whale eye” (when your dog shows the whites of his eyes) typically means he’s anxious.

- Hackles (raised hair): When the fur along your dog’s neck, shoulders, or back stands up, it’s called piloerection. This is akin to goosebumps in people. Hackles are an involuntary reaction that signals arousal. They can indicate negative or positive emotions.

What does fearful dog body language look like?

- Tail: Nervous dogs often have low tails. He might tuck it all the way beneath his belly. Sometimes he’ll wag it quickly back and forth in a tense motion.

- Posture: Leans away from the scary thing. He might crouch, tremble, lower his body and head, or roll onto his side or back (this is sometimes mistaken for an “I want belly rubs” pose).

- Body tension: A fearful dog might move slowly or even freeze completely in place. His features will be rigid.

- Facial expressions: Might show avoidance behaviors like looking away, or display calming signals like lip licking and yawning.

- Ears: Pulled back or pinned ears. They might also swivel quickly to hear the sounds around him, particularly if he’s worried about something out of sight.

- Eyes: Eyes will often be fully open with large pupils. A fearful dog will likely show whale eye.

- Hackles: Fearful dogs may or may not show hackles. It’s not uncommon for different patches of hair to stand up along his back.

An extremely fearful dog might also urinate or defecate when approached. Sometimes scared dogs display aggressive body language (more on that below) when experiencing a fight-or-flight response without the ability to flee. This is a common cause of fear-based leash reactivity.

What does excited or playful dog body language look like?

- Tail: Excited dogs often have quickly wagging tails. It should move in a wide, sweeping motion or even a complete circle (sometimes called “helicopter tail”).

- Posture: Playful dogs often start with a play bow, where they place their front legs down on the ground while wiggling their rumps. They follow this up with exaggerated movements.

- Body tension: An excited dog will be loose and wiggly. He should show minimal muscle tension and only remain still for short moments at a time.

- Facial expressions: Wide, relaxed open mouth. His brow might be slightly furrowed in focus, but his face should not appear tight.

- Ears: Neutral, forward, or pulled back ears can all be seen in excited dogs. They’ll often change position during different phases of a game.

- Eyes: His eyes might be focused on the object of his excitement (like a favorite person or toy). They’re often wide, but not hard or steely.

- Hackles: Some dogs hackle when excited.

What does calm or content dog body language look like?

- Tail: His tail might move in slow sweeping motions back and forth, held at a neutral height. It can also be completely still or hang loosely.

- Posture: A calm, content dog will usually hold a neutral posture. “Neutral” will vary from dog to dog. Generally, he won’t lean towards or away from any specific stimulus.

- Body tension: His body should be loose. Muscles feel soft to the touch (like when a sleepy puppy melts beneath your hand).

- Facial expressions: A calm dog will have relaxed facial features. His mouth might be open or closed.

- Ears: Held a neutral or slightly pinned position.

- Eyes: Soft, relaxed eyes. He will often squint slightly.

- Hackles: Calm dogs typically do not have raised hackles.

What does aggressive dog body language look like?

- Tail: He might wag his tail at a high position in fast, tense movements.

- Posture: Weight either centered over all four feet or leaning slightly forward. He will look large, standing with his head raised above his shoulders.

- Body tension: His body will be rigid. Movements are stiff.

- Facial expressions: A dog displaying aggressive behavior might have a wrinkled muzzle and furrowed brow. He might bare his teeth or pull back his lips.

- Ears: Held pricked in a forward position.

- Eyes: Eyes will often be fully open in a hard stare.

- Hackles: Aggressive dogs often show hackles across their entire backs.

What if my dog gives me mixed body language signals?

Have you ever been excited to visit a friend you haven’t seen in a while…but also a little nervous too? Your dog can experience similar mixed emotions. This can lead to conflicting body language, especially if you’re a new dog parent.

It’s also possible that your dog displays signals in slightly different ways than other canines you meet.

To get through this murkiness, try to look at your dog’s entire body together. Consider the surrounding context. Is he licking his lips because he’s aroused during play—that is, experiencing positive stress? Is he otherwise loose and wiggly? Has he recently had a meal? Or is he stiff with other warning signals, too?

When in doubt, give your dog an opportunity to leave a situation you think might be stressful. One great technique is called “pet, pet, pause”:

- Pet him for a few seconds at a time

- Remove your hand for a moment or two

- If he nudges you, shows wiggly body language, or seems otherwise content, continue petting with intermittent breaks

- If he moves away or seems nervously frozen, give him space

You can do a version of “pet, pet, pause” with things besides affection too. Try giving him the opportunity to turn away from an unfamiliar object on a walk.

Remember your dog is an individual

The above body language distinctions are helpful rules of thumb. Just like humans, though, dogs are unique individuals.

One of the most important things you can do with your dog is spend time getting to know each other. Over time, you’ll be able to pattern match which signals (like vocalizations, body posture, or facial expressions) typically indicate certain needs (like to use the bathroom or be removed from an uncomfortable situation).

The more you listen to your dog and communicate back in ways he can understand, the more you fill his trust battery.

Key differences between dogs and people

We have opposite primary senses

A dog’s primary sense is smell, followed by hearing and then sight. This is the exact opposite for us humans. We experience the world through our eyes first. Unless a scent is particularly offensive or overpowering, smell is typically just an afterthought.

People have episodic memory, dogs have an associative one

Humans recall separate events in their surrounding context (like the location, time, and chronology of what happened before).

Dogs remember general associations (“grabbing leash = walk”) rather than specific instances (what else was going on in the room on a certain day you grabbed the leash).

Canines and primates have different instincts

We don’t have the same social norms or ideas of what’s rude and polite. A few examples:

- It’s natural for our dogs to chase prey and scavenge for food. We typically don’t understand those things (and often refer to them as “problem” behaviors).

- It’s natural for us to greet each other face to face with upright posture. This type of introduction can feel confrontational to our dogs.

Our body language can mean different things

We share some body language tendencies with our dogs (like that we both fidget when nervous and move loosely when comfortable).

Many behaviors mean different things in canines versus humans though. Dogs are more likely to yawn when worried rather than tired. Their wide-mouthed pants can indicate heat exhaustion or stress rather than a happy smile.

The one key similarity—we're both social mammals

While some of us are more introverted than others, dogs and people all have a basic need to form social bonds.

“Being socially connected is our brain’s passion,” says Matthew Lieberman, professor of psychology, psychiatry, and biobehavioral science and author of Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect. “It’s been baked into our operating system for tens of millions of years.”